At 12,000 ft above sea level, Shigarthang, located in Skardu, Pakistan, is believed to be among the world’s highest human settlements. Nearly 150 houses made by stacks of stones and woods keep together some 1,500 inhabitants who are facing the harshness of cold weather for centuries.

When the temperature goes beyond minus 25 Celsius in the shrilling winters, these people lock themselves in their houses and survive on the preserved barley, milk, and butter from their animals.

With snow all over as thick as 10 feet, these people remain in a state of desolation for several months.

Approximately 50 KM from Skardu, this beautiful gem of Gilgit Baltistan with breathtaking scenic views lies on the west of Indus valley. The only path that goes to this valley passes through Kachura. It’s a rocky terrain that tests the nerves and skills of even experienced drivers. Only a few local drivers can make it to the top.

Muhammad Ali Abbas, 50, is one of the few drivers from Kachura who dares to enjoy taking tourists to the plains of Shigarthang. Abbas has spent nearly 10 years of his life raising animals in the mountains of Shigarthang; he knows every rock of this off-road by heart.

His jeep crawls for 3 hours on this rough terrain of almost 30 km that starts from the Kachura village. Although the journey is full of adventure, Abbas can only make less than a dozen rides during summer.

What if our car gets broken down here, I asked Abbas during our way up, “we will have to go on feet, and I will bring a mechanic tomorrow with the necessary tools. There is no risk of theft to my car if I leave it here the whole night,” he replied with a smile.

“We don’t normally tell tourists about this valley because the path is horrific, the ride is jumpy, and it takes a heavy toll on their bodies and minds,” Abbas revealed.

Not long ago, just 40 years back, these people didn’t know there was a world outside their village.

When the government established a first rocky track to this village, the folks reportedly offered grass and water to the vehicles, as if they looked like animals, when the engineers reached.

It was only a matter of weeks when the landslide destroyed that track. Once again, the village became inaccessible for the next two-and-a-half decade until the people of Kachura and Shigarthang, with some NGOs’ financial support, built the existing track in 1998. The track is still operative today.

Since there are a handful of vehicles, including Abbas’ that can go till the top, every 10th day, a jeep leaves from the city for Shigarthang carrying eatables and necessary items along with the villagers who go back to their homes to visit their families. The same vehicle returns to the town after 10 days.

For the outside world, their life seems simple and quite similar to what mother nature had given them, but the fact that there are no other means of transportation, no electricity, no mobile phones adds to their miseries.

They use homemade medicines for the day to day medical issues, although the government upgraded the local ‘Hikmat’ to a dispensary, it can only take care of minor problems.

If someone gets sick, the patient is brought down on a stretcher on feet, which takes nearly 6 to 8 hours. Many times, the patient dies on the way.

The deprival of modern-day facilities also makes them strong. They feed themselves only what they grow. Their animals are everything they have.

They are famous for the butter they store for years by burying it underground in their houses. They conserve it for years and only use it on social occasions as gifts. It is a matter of pride for them; the older it is, the more valuable it becomes. The locals believe it is full of nutrition and effective in asthma-related problems.

It was a Sunday when we visited Shigarthang, and we were welcomed by a group of chanting children who accompanied us all the way where ever we went till we parted in the afternoon.

Other than Abbas, who knew them, we were alien to them. Women and girls were camera shy, but they were very comfortable with our female members otherwise. Since most of the men were out on the work to clear some landslide blockage, we had the company of boys to enjoy our moments.

There is a government-run primary school where children can only learn from a locally hired school teacher. For further studies, they either have to move to the city – Skardu or Gilgit in this case, or they get themselves busy with their traditional cultivation.

Jobs and business opportunities for Shigarthang people are as bleak as their cold nights and those who get hold of some education from GB colleges and universities. They are not considered and accepted in universities and for the jobs in other parts of the country.

A Shigarthang woman starts her day around 5 AM, leaves the house to collect the woods. Usually, she carries 20 kg of wood back home every day, followed by everyday chores. Many of them are tasked to work in the fields besides taking care of the children.

While we were on our way to Shigarthang, we could see small solar plates here and there on some rooftops of houses on the route, but Shigarthang people don’t seem interested in changing their ancestral way of life. They are still comfortable with lanterns.

They are disconnected from the world, but even today, they are pure and honest. Our host told us that no police case had been registered in Kachura and Shigarthang during the last 25 years. The crime rate is zero, and people don’t like to get involved in serious disputes. Matters are usually resolved at the Jirga level in 3 to 4 days.

Shigarthang is a place unique in its way. The fragrance of wild roses, apricot, and walnut trees engulf the entire land. In summers, when the water is high, the river roars that only the strong-hearted can bear it.

According to locals, besides Apple, the valley produces over 70 kinds of Apricots. Unfortunately, 80% of the fruit gets wasted as there is no proper connectivity between Shigarthang and the world.

The area offers large reservoirs of precious stones, iron, and gold. Although locals don’t have the means to benefit from what nature has gifted them, outside contractors extract ruby, emeralds, and various other expensive gemstones and sell them for millions in the international market.

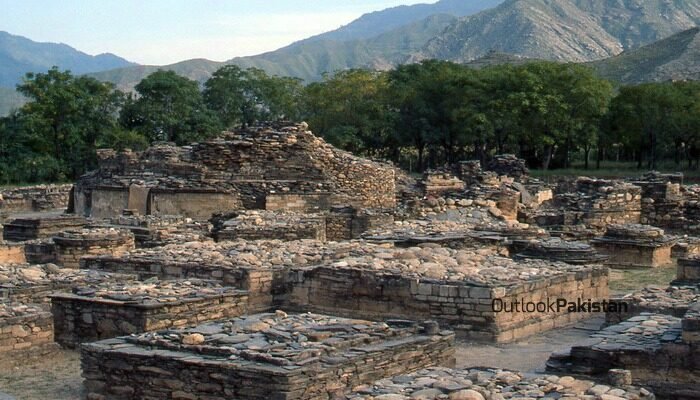

Few of the families of Shigarthang have migrated to the cities in search of a better future, but many of them don’t want to end their 700 years old history that started with Buddhism.

“We don’t want huge commercialization of the area, but the basic needs like electricity, transportation, roads, health, and education facilities are the right of people of Shigarthang,” highlighted an elder who also greeted us with a traditional dish, tea, and lassi.

For them, time is still for centuries. Abbas doesn’t believe the world will ever look to them.

It is the time when people and the government must come forward and ensure a bright future for all the remote communities like Shigarthang in Pakistan.

We in metropolitans keep learning many things every day and call ourselves more civilized, but in contrast, every passerby in Shigarthang and Kachura, men or women, said hello (Salam) that we never experience in our cities.

We are really thankful to the management of Caprafal, who helped us in making this journey possible.